Weaving Jamdani Wonders

Communities of the weavers of Jamdani saris flourished with Mughal patronage in Varanasi. KAMALA, a festival organised by the Crafts Council of India, will showcase exquisite creations of Jamdani at the Lalit Kala Academy, Chennai, next month.

Apart from being the seat of culture with its poets, philosophers, musicians and textiles, what is prominent in Varanasi is the rich brocades, the soft jamdani and the versatile draw loom. The jamdani is a great technical achievement of Indian weavers and it means “loom-embroidered,” truly one of the most exquisite products of Indian handloom fabrics. The word jamdani is of Persian origin – ‘jam' means flower, and ‘dani' means vase or container. In Pupul Jayakar's words, it is a cloth that is “light to the body, that moves to the gentlest breeze, a cloth of great beauty recalling flowers and running water and moonlight…” indicating the delicacy of its colour and weave. The Mughal aristocracy lifted the textile to its heights, when they captured the centres and these woven dreams were presented in all their diaphanous beauty to the Emperors year after year. The luminous gold in the sheer tissues is so subtle and captivating.

Travelling techniques

Varanasi bears the tradition of weaving fine cotton fabrics, but the more popular silks may have been acquired from migratory weavers from Gujarat in the mid-eighteenth century. The cotton fabrics are woven loosely with fine cotton yarn and brocaded in the jamdani technique with floral sprays or scrolls in metal thread or cotton yarns and bear similarity to the cotton jamdanis of Bengal. Weavers turned to silk and organzas because they fetch a better price for labour.

The design range is mind boggling. There are geometric motifs, floral creepers and buttis, the ubiquitious paisley, even a bunch of flowers. Persia, China, Tibet and Europe have undoubtedly influenced the jamdani weave. This is a craft that has been nurtured by royal kharkanas supported by royalty or nobility from Varanasi, Avadh and Rampur. The Mughals have contributed enormously to this splendiferous craft through their unstinted patronage.The delicate fabric requires immense weaving skill and consists of woven motifs in additional weft over a transparent and delicate background, which is often in a pale colour. Very often the main body of the textile is woven in unbleached cotton yarn and the design is woven in bleached yarn in threads heavier in count than the background, which makes the subtle contrast exquisitely beautiful. What sensuous pleasure to watch shadow on sheer transparency, in attenuated colour tones! The extra weft is worked to give the special effect to the motifs, placing the design placed under the weaving frame. The jamdani butta was an ornamentation used often in ancient India. This specialised loom embroidery entailed the working of exquisite floral or geometric motifs to cover the entire body of the cloth, using bamboo spindles separately for each motif (and not any technical contrivance), like the naksh to help the weaver formulate his design. Very fine yarn is used which could easily break if the weaver is careless. The traditional motifs in jamdanis are chameli, (jasmine) panna hazaar (thousand emeralds), genda butti (marigold flowers) pan buti (leaf form), and lehari (diagonal stripes).Today the treadle operated jacquards have replaced the naqsha as a pattern device and has saved substantially time and labour, doing away with the drawperson.

It was during Mughal rule and patronage that the muslin weaving in Bengal reached heights and the legendary Ab-i-Rawan or “flowing water” was woven. The locally grown cotton was so fine that it lent itself perfectly to the weaving of softest of muslins. Sir George Watt during the British reign is said to have been amazed at its sheer delicacy when he passed the delicate fabric through a ring. Somehow, unlike in other weaving centres, this craft has been surviving, with very little change, except that the looms used today are fly shuttle looms as opposed to the pit looms of the olden days.

It is said that on one occasion, Emperor Aurangazeb gave his daughter Princess Zeb-Un-Nissa a severe dressing down for wearing skimpy clothes. She retorted that on the other hand she was fully clothed, with her seven jamas, or garments on her pencil slim body! So sheer were the fabrics that she wore, that it was deceptive. The jamdani muslin was and still is one of the most celebrated and sophisticated Indian textiles, even in its modern vocabulary.

Some saris are patterned with meenakari (enamel work) where the background is in silk and the zari used for the design. The classic khinkhab whose noble antecedents were favoured by Mughals and the courts of Northern India, is gold twilled, compacted with motifs sometimes married to silver in the single motif. These gold and silver brocades are converted into yardage for luxury furnishing and the heavy brocades converted to garments for the nobility.

The draw loom is a complex hand loom for weaving figured textiles. The design harness used in Varanasi is one of great complexity and width and it is the cross cords which lift the warp for executing the pattern. All these intricate arrangement of cords form the design module called the naqsha. The designing of the naqsha was done by extremely skilled naqshabands, a diminishing set of artisans. Today the dependency is removed with the introduction of the treadle operated jacquards, which have saved substantially, labour and time, and the extra drawperson. With the decline of Mughal patronage the craftspersons migrated to other centres and Avadh became a centre for jamdani weaving.

Going natural

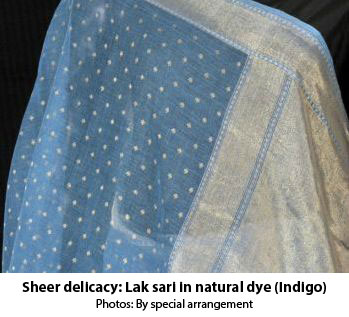

In a bid to address the contemporary market Cholapur clusters in Varanasi have been working on a new range, in natural dyes like Allium Sepah (Onion Skin), Jathropha Gossipifolia (ratanjot), Acacia Chundra (Katha), Indigofera Tinctoria(Indigo), Punica Granatum (Pomegranate), and Hellianthus annus (Sunflower). These natural dyes have been specially developed with the help of Weavers' Service Centre — Varanasi. This collection “Shabnam …Lak weaves in Natural Dyes” will be showcased at the exhibition.

Weavers in Varanasi faced the impact of Chinese “Benares brocade saris” imported at a fraction of local prices. Again this is a story of utter poverty and despair and the weavers unwilling to remain shackled to a crippling tradition. Thousands of weavers around Varanasi became pawns on the chessboard of a capitalist system of merchants, brokers and bureaucracy. There are different reasons in every state for traditional weavers to move away, but craft NGOs together with the Government have to protect their interests and give them sufficient incentive to carry on with their centuries -old skills.

Sabita Radhakrishna is a Chennai based freelance writer in craft and textiles and may be contacted at kittsasbi@dataone.in

Exquisite fare

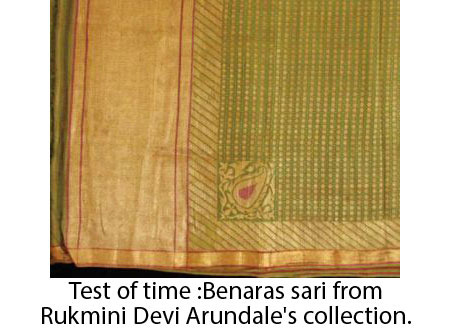

Crafts Council of India's exhibition KAMALA, a classic revival of heritage textiles will showcase exquisite Benares saris along with reproductions of some of the finest heritage textiles on December 16 and 17 2010 at the Lalit Kala Akademi, Chennai.